The Dutch-Norwegian hunt for atomic secrets

18 February 2025

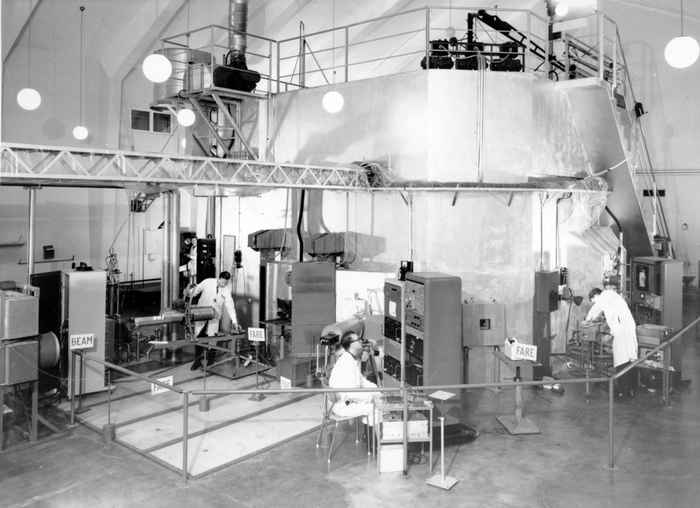

After World War II, the United States protected its monopoly on nuclear weapons through an extreme policy of secrecy and control over nuclear materials. Only after 1953 did this policy begin to ease. It was precisely during that period - between 1945 and 1954 - that the Netherlands and Norway built a joint nuclear reactor. Using that reactor, they were able to conduct independent research and measure data that was still classified in the United States.

The collaboration provided Kleemans with a unique opportunity to study how scientists navigated the tension between open science and state secrets. ‘The Dutch-Norwegian project went against the prevailing secrecy policies. How did scientists deal with these restrictions, and how did they still manage to access crucial knowledge?’

Uranium and heavy water

‘There was initially an open culture in nuclear physics, but after the discovery of nuclear fission in 1938, secrecy became increasingly important,’ Kleemans explains. ‘During World War II and the development of the first nuclear weapons, nuclear research became entirely classified.’

Yet, as early as 1939—just after the discovery that a chain reaction in uranium could be a vast energy source—the Dutch government secretly purchased 10 tonnes of uranium oxide. Norway, in turn, had a unique facility for producing heavy water, a crucial component of nuclear reactors. These two key ingredients formed the foundation for close Dutch-Norwegian collaboration in the nuclear field.

Oppenheimer’s advice

After World War II, the Netherlands and Norway sought to continue their nuclear research while also circumventing American restrictions. Scientists leveraged their international networks and strategic deals, such as uranium exchanges for fuel rods, to obtain the necessary knowledge and materials and get their reactor operational.

J. Robert Oppenheimer, known as the ‘father’ of the atomic bomb, played an indirect role in this collaboration. ‘When the Dutch physicist Hans Kramers sought support for the reactor in the U.S., Oppenheimer advised him on how to operate within American policy,’ Kleemans explains. ‘Thanks in part to his influence, the United States granted the Netherlands and Norway permission to proceed with their nuclear project.’

Easing of American control

After the Soviet Union’s first successful nuclear test in 1949, U.S. control over nuclear technology became less stringent, and more information was gradually released. However, the Netherlands and Norway also took independent initiatives to expand their knowledge.

‘In 1953, the Dutch physicist Kistemaker developed a device to enrich uranium. The Dutch-Norwegian collaboration used this technology for experiments the American versions of which were still classified. For a long time, it was believed that these experiments contributed to a more open American policy. In reality, the U.S. was primarily guided by its nuclear advantage over the Soviet Union when deciding on greater transparency,’ Kleemans explains.

The spread of secret nuclear knowledge and technology required three essential elementsMachiel Kleemans

Secrecy as a tool of power

Kleemans concludes that the spread of secret nuclear knowledge and technology required three essential elements: the exchange of materials, scientific networks, and political support. His research also reveals the secrecy dilemma. ‘Openness and secrecy are not necessarily opposites,’ Kleemans states. ‘Both served as tools of control, and changes in secrecy policies reflected shifting power dynamics within Cold War science.’

Still relevant today

The Dutch and Norwegian initiatives were curtailed in 1961 due to stricter political oversight. However, the mechanisms of strategic materials, networks, and political backing remain relevant today. ‘Consider ASML’s chip technology, the development of quantum computing, or genetic engineering. Scientists and policymakers continue to grapple with the same questions about secrecy and openness, as well as the availability of materials and techniques,’ says Kleemans.

Thesis details

Machiel Kleemans, 2025, The Secrecy and Science of Cold War Atoms in the Netherlands and Norway. Supervisor: Prof. J.A.E.F. van Dongen, Co-supervisor: Prof. E.L.M.P. Laenen.

Time and Location

Wednesday, February 19, 11:00-12:30, Aula, Amsterdam