Spherical assemblies of nanocrystals

11 February 2026

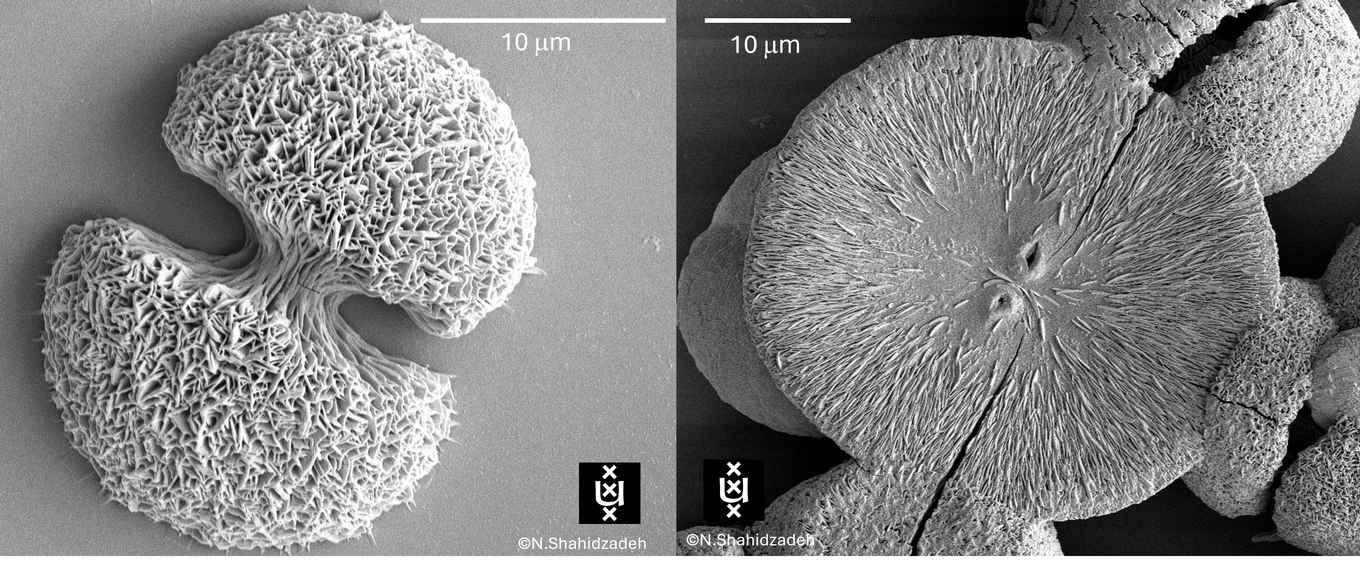

A new study done in Shahidzadeh’s lab at the Institute of Physics / Van der Waals Zeeman-institute, reveals how neatly ordered (hemi-) spherical or pancake like structures in nature can emerge from completely disordered salt solutions. Moreover, scientists can now harness these structures to create advanced materials.

Structures like tiny sea urchins

Take some ordinary table salt and dissolve it in water. The salt breaks down into its tiniest constituents, ions – atoms with some electron charges added or removed. The same process can be carried out for many other materials. When the water evaporates, crystallization – the same process that forms snowflakes or rock candy – transforms these disordered mixtures of ions into elegant, structured forms: crystals. This process of crystallization underlies a wide array of techniques, from purifying medicines to crafting high performance materials such as silicon wafers that power modern technologies.

The researchers now show that for mixtures of different ions, something extraordinary occurs. Instead of forming a single flawless crystal, the matter can organize itself into so-called spherulites — mesmerizing, spherical structures that sprout like tiny sea urchins or coral heads under the microscope. They uncovered how subtle shifts in ion composition — specifically, the presence of so-called divalent ions in highly viscous mixed sulfate solutions — drive the formation of well-organized sodium sulfate nanocrystals into spherulitic shapes at room temperature.

Tess Heeremans, first author of the study and now a PhD student at AMOLF, explains how the discovery came about. “We stumbled upon the spherulites by surprise during my master’s internship with Noushine, one of those magical moments in the lab. Once we saw them evolve from our salty mixtures under the microscope, we couldn’t look away — it was so cool! I thought: Is this a crystal? It does not look like it at all! That curiosity ended up steering my master thesis in a new direction and resulted with hard work and collaboration in a publication which I am extremely proud of.”

Beauty serves as a record

The work shows how subtle variations in composition, viscosity and evaporation rate determine whether the crystals grow as open, spiky forms, dense spheres, or well-defined regular lattices. The work shows the amazing beauty of Nature, but the discovery also has practical applications. Beyond decoding fossil-like mineral textures once mistaken for biological remains, it offers a pathway to engineer materials with intricate internal architectures and exceptionally large surface area with designs written by the physics of nonequilibrium growth.

As Heeremans puts it: “Spherulites may look magical, but their beauty serves as record; like a snowflake shaped by the clouds it grew in, a spherulite reflects the environment of its formation. By identifying key growth conditions, we can direct crystalline salts to form these high surface-to-volume structures, which can drastically change the properties of many materials.”

Publication

Controlled spherulitic crystal growth from salt mixtures. Tess Heeremans, Simon Lépinay, Romane Le Dizès Castell, Isa Yusuf, Paul Kolpakov, Daniel Bonn, Michael Steiger and Noushine Shahidzadeh. Communications Chemistry, published 15 January 2026, currently in press.