What friction and red traffic lights have in common

29 April 2025

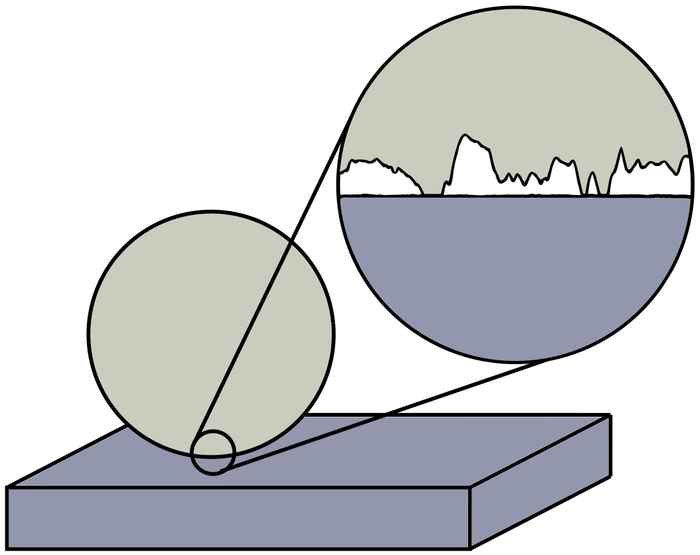

In their experiment, Liang Peng, Thibault Roch, Daniel Bonn and Bart Weber pressed a smooth silicon surface against a rough one. The researchers, from the University of Amsterdam and the Advanced Research Center for Nanolithography, then explored how the friction behaved when the strength with which the two surfaces are pressed together was varied. Does it get harder to slide the two surfaces along one another when one presses harder? And, importantly: why?

Understanding the why

It turned out that the amount of friction depends on a very interesting underlying process. At low applied force, only one tiny contact point – a so-called “asperity” – bears the load, and it needs to be pushed hard before it slips. However, as the force perpendicular to the interface increases, many asperities come into contact. The team discovered that in this situation, once a few asperities start slipping, others are triggered to follow—just like the first bold pedestrians prompt a crowd to cross.

As a result, and perhaps counterintuitively, the surface starts sliding more easily, and the relative resistance to motion – the so-called static friction coefficient – decreases. Using a simple mathematical model to support their experiments, the researchers were able to show that the crowd-like behavior of the asperities explains why static friction weakens at higher loads.

From semiconductors to earthquakes

The results have applications at small and large scales. At small scales, in the semiconductor industry, the construction of electronic devices often requires clamping curved surfaces to a flat table. This results in an interface that is right at the boundary of slipping and not slipping. The new research explains how the onset of sliding is influenced by the scale of the contact, which is important to know when accurately constructing devices using all sorts of materials.

At larger scales, earthquakes are the result of the onset of sliding between sections of the earth’s crust. Understanding how this slip starts, and what effects become important when interfaces get bigger, can support our understanding of how earthquakes come about, and can help predicting them in the future.

Publication

The decrease of static friction coefficient with interface growth from single to multi-asperity contact, Liang Peng, Thibault Roch, Daniel Bonn, and Bart Weber. Physical Review Letters 134 (2025) 176202.