Dark matter even more elusive than previously thought

Dark matter might be disappearing and sending its signal – but not very fast – in dwarf satellite galaxies

17 September 2020

The nature of dark matter remains one of the greatest mysteries in physics. The question whether this missing matter in the universe consists of particles, and if so, of which type, is still unanswered.

From big bang to present

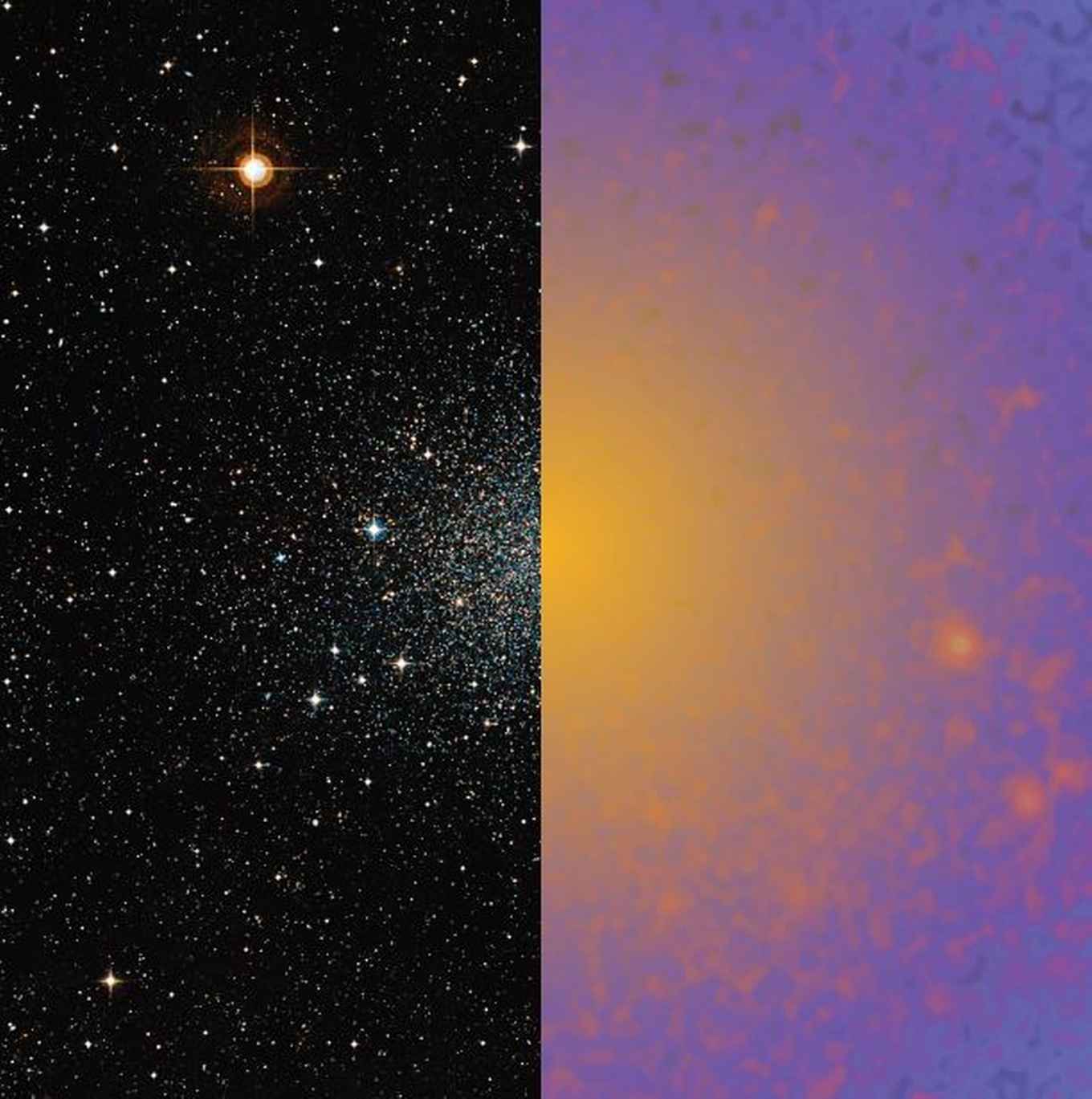

Revealing the nature of dark matter might be achieved by looking for faint signatures coming from pairs of dark matter particles. These pairs may annihilate each other and turn into gamma-ray light that could be observed. Some of the best targets for such a search strategy, using gamma-ray telescopes such as the Fermi satellite, are dwarf spheroidal galaxies – small satellite galaxies that are trapped in the gravitational pull of our own Milky Way. Dwarf galaxies are full of dark matter but little else, meaning they are nearly pristine laboratories to look for the tell-tale signatures of dark matter annihilation without the pesky complications of other astronomical phenomena.

In order to perform the search, the scientists combined theoretical and observational methods to put together the first ‘end to end’ analysis that models the dwarf galaxies in their cosmic context.

Shin’ichiro Ando, of the Institute of Physics at the University of Amsterdam, said: “Our method starts at the big bang, follows the evolution of dark matter and the growth of galaxies across cosmic time, and uses this as the basis to understand how dark matter might be distributed within the individual dwarf galaxies we see in the sky today. This understanding is then used as the basis to search for the gamma-ray signal which reveals information about the microscopic properties of dark matter particles.”

Weak signal

Dr Alex Geringer-Sameth, from the Department of Mathematics at Imperial College London, said: “We were surprised to find that including all of the science about how the universe grows and evolves over eons – something prior work tended to neglect – has a very strong impact on the dark matter conclusions we can draw from the dwarf galaxies today in our immediate neighborhood.”

In particular, the team concluded that the expected signal of the dark matter annihilation is much weaker than earlier estimates. Simply put: dark matter is harder to detect using dwarf galaxies than previously expected. Adopting the more holistic analysis therefore implies, counter-intuitively, that the gamma-ray data actually tells scientists less about dark matter than they thought it did previously. One immediate consequence is that there is still a possibility that dark matter annihilation explains one of the great current astronomical mysteries — the anomalous and unexplained gamma-ray glow that we see emerging from the center of our own galaxy. Until now, it was difficult to see how dark matter annihilation could power the galactic center anomaly but avoid generating a similar signal from the dwarf galaxies.

The results, that were published in Physical Review D Rapid Communications this week, strongly call for revising one of the key search strategies towards discovery of dark matter particles and the quest for physics beyond the Standard Model.

Publication details

Structure formation models weaken limits on WIMP dark matter from dwarf spheroidal galaxies, Shin’ichiro Ando, Alex Geringer-Sameth, Nagisa Hiroshima, Sebastian Hoof, Roberto Trotta, and Matthew G. Walker, Phys. Rev. D 102, 061302(R) (2020).